|

|

|

|

LECTURE ON "BEAUTY" BY MR. F. M. SUTCLIFFE.

From the Whitby Gazette - Friday 23 March 1900

A most entertaining and instructive lecture was delivered by Mr. F. M. Sutcliffe at the Trinity Lecture Hall, Flowergate, on Tuesday evening, under the auspices of the Presbyterian Mutual Improvement Society. There was a very large attendance.

Mr. J. M. Jones presided, and in his opening remarks said that Mr. Sutcliffe was so accustomed to the use of negatives that when they waited upon him, and asked him to deliver a lecture that evening, they were afraid he would give them a negative reply. In other places than Whitby Mr. Sutcliffe would be welcomed on account of his position in the photographic world; but they had every reason to give a warmer tone to their welcome, because all present knew his ready willingness to aid any movement for the benefit of Whitby and its inhabitants. All the members of the Society welcomed him very heartily that evening, and all present looked forward with very great pleasure and interest to his lecture. He then introduced the lecturer.

After a few preliminary remarks Mr. Sutcliffe said that it was rather of Whitby than of "Beauty" that he wished to speak that night. They all knew as well he did that Whitby depended very largely on beauty for its existence. If it were not beautiful, strangers would not come here with their pockets full of money.

In the past Whitby had other things to depend on — whale fishing, ship building, ship-repairing and jet; but now if it were not for its beauty it would be badly off. There was no fear of Whitby’s visiting season disappearing as long as her beauty remained, for people were becoming more alive every day to the importance of cultivating a sense of the beautiful. They had only to look around them to see the difference between the taste of to-day and that of fifty years ago.

It was hardly less than a miracle that the eyes of so many had been opened - that they now saw beauty where before they saw nothing. He believed that one of the most sincere forms of worship, one which is most acceptable to the Maker of everything, is the worship of beauty.

This world is beautiful, and it was ungrateful of them if they did not try to look and appreciate all this beauty. There were many good people who said grace before and after meals, whom, he feared, did not say grace when they saw a beautiful sunset or even a beautiful flower. It was impossible to see beauty if they never looked for it. They could not see beauty if their eyes were for ever in their pockets. Some were blind to everything but the glitter of gold, and deaf to all music but the crackle of banknotes. We could not worship both God and Mammon. Some sacrifice must be made; time must be given to one or the other.

The greatest apostle of all that is good and right of this age, Mr. Ruskin, had told them how the worship of Mammon turns men into demons, and prevents them from ever reaching a higher life. If it is an acceptable thing to be grateful for beauty where we see it, it must be still more so to try and make this world more beautiful.

Whitby is admitted by those who have travelled much, and by those whose opinion is to be valued - he meant by such men as the late Russell Lowell and the late George Du Maurier, to be one of the most beautiful towns in England. (Applause.)

We should, therefore, be proud of our old town, and be ever on the alert to see that no barbarian spoils any of the beauty of this precious heritage left to us by our forefathers.' We should protect its beauty and stand up and fight for it if need be, as a manly lover would stand up and fight any ruffian who tried to injure his lady-love, for this beauty is not of our making, has been made by men who have long been sleeping near the old church.

It is well-known that in all ages people have expressed themselves more plainly by their architecture than by anything else; it is not difficult to read the characters of people by looking at the houses they build.

Now if we stand on the Pier and look across old Whitby, and examine the old houses one by one, we shall feel that the men who built them must have possessed sturdy qualities, often sadly lacking in this present day, for it is by the houses of the people, rather than their churches or town halls, that we can tell what kind of men they were. For each man builds his house for himself, whereas their churches were often built by strangers.

No doubt the honesty of purpose and the manly simplicity and strength which we see reflected from all the old houses in Whitby are due to their having had as an example such a one as can be found nowhere else - the Abbey. (A full length view of the Abbey from the southwest was here thrown upon the screen.) Not only as a whole; but taken in detail, the Abbey must have been, when complete, such a building as we now cannot imagine.

He then read what the late Mr. C. N. Armfield said of this Abbey of ours, in which he stated that amidst these ruins of ancient glory, I do not hesitate to declare that we are looking upon the most lovely specimen of the most lovely Gothic architecture in the world." Two views of the interior of the Abbey were then thrown on the screen, and their beauties pointed out by the lecturer.

As a contrast, a bit of modern Whitby was shown - a picture of a house which was represented to be built of large blocks of stone, but in reality it was only painted skin, being cemented over the top. He said they might as well paint buttons and pockets on their bodies, and pretend they were dressed. He had often asked builders why they chalked their cement walls into squares which are supposed to look like stones, but they never could tell him. (Laughter.)

Particular attention was drawn to some very ugly iron railings in this picture, then compared the cement walls to the rough-cast of fifty years ago, showing a view of Robin Hood's Bay as an illustration.

One great charm of Whitby laid in its red roofs. These were beautiful in colour, and age had made them more so. Red tiles were beautiful because they were the natural product of the soil - they were part of the earth below the houses; whereas slates were something from another land, like part of another tune slipped in by mistake.

During the past fifty years, artists had come from all parts of the world to paint our red roofs and brown sails; the pictures they had painted had gone all over the world, and had advertised the place, and brought people here who would otherwise never have come. Our red roofs were more valuable than they thought; even looked on from the lowest standpoint by those who worshipped the goddess of getting on, they were worth keeping. Yet the improver uses slates.

As they knew, Whitby was built on both sides of the river, yet, while one side was beautiful - at times exquisitely so - the other side, while possessing even better natural formation, being more stable, and not given to slipping away, was ugly. While the East side gave them charming pictures of colour, it gave them equally beautiful formations of line.

Perhaps they had never asked themselves the question: Why is the East town so beautiful ? Before they could answer this question, they must ask themselves: What is beauty ? and why do they sometimes call things beautiful ?

There was an axiom, "Beauty lies in the eye of the beholder." There they had the gist of the matter. Beauty made itself felt through the eye. Whether they derived any pleasure from the sight of anything, depended on the way certain nerves which ran from the eye to the brain were affected.

Taking the colour the East Cliff first - for colour was of more importance than form, though foreigners laugh at English for being so colour-blind - the colour of the sky, and the sea, and fields, and the trees, and the flowers, affects our senses long before they look at shape of these things. The East Cliff is beautiful in colour for the same reason that a well-dressed woman is pleasant to look on. A well-dressed woman does not wear red jacket, blue dress, and green hat, and yellow parasol. Our eye would have to make too many jumps to a costume of that description, to be pleased. The East Cliff was beautiful because it was well dressed. The clothing which man has given it was all of one colour, the colour of burnt clay, red brick, and red tile.

We can stand on the West Cliff and our eye roams about on all this colour with pleasure, yet, it does not weary, for this red colour will bear closer inspection still. It is not one monotonous red, as a house end would be if washed with red cement, but the red is overlaid here and there with other colours, so that the red appears brown here, and grey there. Of the East Cliff, which man has not clothed with buildings, we see the reddish clay, the grey rock, and the green grass.

At times, this grey rock and green grass did not please our eye. It has to jump to get from one to the other; perhaps if they left the green grass above and never cut it, it would appear long and yellow. He thought they would agree with him that the East Cliff looks its best when the golden or crimson rays of the setting sun make the grey rock and green grass less grey and less green, and makes them more of the colour of the red roofs and red houses. There are evenings every summer when the Cliff appears so, and when heaven seemed very near to earth.

He should like someone suggest to the Pier Band that on such evenings they should refrain from playing, or, if play they must, to play something that would not jar with the sunset colouring. If some woman's or boy's voice could be heard singing the Te Deum, or something more in keeping than "Chin, Chin, China-Man," the solemn silence which they felt at those times would, he thought, be deepened.

While this part of the lecture was being delivered, two fine pictures of the East Cliff were shown.

The Lecturer then proceeded to criticise the way in which some of the more recent structures had been built to the detriment of their neighbours. He then went on to say that there were evidences in many of the older buildings in Whitby of a great reverence for beauty.

There were evidences, too, that the workmen of Whitby were skilled wood carvers long before jet carving came into fashion. Many of the old doorways, such as the one then depicted, show that no pains were spared to make the houses, and especially that part of the house which is most seen, the door, beautiful. He would have them notice the carving on the frame, which was all hand work.

The East Cliff was not without its blots, blots which have been made on its fair page within the last thirty years. When he first remembered it, forty years ago, it was almost without flaw. The first smear was, he believed, made in pulling down some old houses near the bridge and replacing them with yellow brick and blue slates; then the Market was built, and then the Wesleyan Chapel got too proud to wear its beautiful weather-painted red coat any longer, and put on the hideous shining Welsh garment it now wears. Some ugly jet shops were put up, and various other slated roofs, but he hoped the next century would see these eyesores removed.

Several views of old doorways and shop fronts, showing beautiful work, were next given, and described by the lecturer, who remarked that they would see what Whitby shops were like in the good old days before that horrible thing, plate-glass, was introduced. Many people who have had the old-fashioned small panes taken out of their shops now tell him they would give anything to have them back again as they were in the days of Sylvia's lovers.

During the past few years there had been a good deal of building round Whitby. They would have seen that an attempt had been made make the newly-built houses in keeping with the rest of the town using tiles instead of slates, and by using well burnt red bricks instead of white ones or cement. Some of these new houses were much more successful from an artistic point of view than others. Sometimes they watched a house nearing completion and found no fault with its design till the roof was put on. Sometimes, he understood, the owner upsets the architect's plans at the last moment by deciding on having slates after all. In other cases it was sometimes the finishing touches which spoilt the picture.

There was presented on the screen the lower part of a new house. At first sight it seemed pleasing, and a successful attempt at making a house front beautiful, but for want of a little more care the attempt was a failure. He need hardly point out where the wrong notes were. They would all have felt them to be the lines sloping in opposite directions. They had no harmony with the other part of the fabric.

There were other examples, far more irritating than these, of useless ornament. Undoubtedly, the most beautiful house which has been built lately was Flowergate Cross (a picture of which was shown). That house had both a good roof and fine chimneys, and the front was not painfully symmetrical. One window was not the exact counterpart of the one opposite. There was nothing so wearisome as monotony, and nothing so tiring as symmetry. They would have read in the papers what Mr. Miles Gaskell said at Wakefield the other day: "that he believed the people in the Twentieth Century would repair the errors which have been committed in the Nineteenth, and instead of having no ambition but to fill their pockets with money, their aim in life would be health and beauty. He said that many men whose lives have been spent in money-making would have been more usefully spent had they done nothing but pick up the straws and orange peel which disfigure our streets." (Applause.)

When we turn to the West Cliff, we find that the people of the Twentieth Century will have far more sins against the Goddess of Beauty repair than on the other side. What is that which makes the West Cliff look so uninteresting ? Is it not that the houses on it are wanting in character ? There was no individuality about any of them. They all look as if they had been built by a company for the sake of profit rather than by a number of differently moulded people to live in. They would see that all those houses had little or no roof.

Now in this part of the world, where, when it was not snowing it was generally raining, a good roof was of the greatest importance, for the same reason, owing to the coldness of our climate they must have fires and chimneys, so the chimneys were of great importance too. Here was shown view of a house at How Wath with a very bold chimney built outside of the line of the honse.

Our forefathers felt the need of good roofs, and paid much attention to the building of good roofs. They had here a view of some old houses across the water, which showed two fine old roofs. Did not those roofs give that strength and character which we missed so in the houses on the West Cliff?

They must have noticed that whenever a beautiful building was put up in Whitby that an ugly one grew up alongside it. It was a case of "the beauty and the beast," only very often the beast stood out so far that it hid the beauty altogether. The Court House in Spring Hill was a beautiful building, as the home of Justice and Law should be; but it was so surrounded with other buildings that his camera would not take in any more. It was the late Mr. Charles Bagnall who first pointed out that all our good buildings but the Abbey were hidden out of sight.

There was a view of one of the most beautiful modern buildings in Whitby - the York City and County Bank. They would see how it harmonised with the old building near to it, and how much more character there was in its lines than in the ugly St. Hilda's Hall behind it. It was a great pity that the builders of other property had not followed the example of the architect of this bank, for the other buildings facing the Dock End were anything but beautiful.

He had mentioned that the livelihood of Whitby depended its beauty. One day early last summer he was breakfasting at an hotel near the Station. Opposite to him sat a gentleman who emptied his soul of its grievances. He said he had come in by the ten o'clock train the previous evening to look for a house to bring his family to, and that before breakfast that morning he had been for a walk in the sunshine to see what kind of a place Whitby was.

He (the lecturer) gathered from his description, and the irritation he was suffering from, that he had gone from Victoria Square along the Dock End to the Bridge and back again. He said he had seen quite enough of Whitby, and that he was off to try Saltburn. How many thousands more go to try Saltburn when they have seen the Dock End, they did not know. Why the finest sight in Europe , (it might beat Trafalgar Square into fits) should be nothing more than a dirty lane with tumbledown houses and dust bins and tumbler carts, was past comprehension. (Applause.)

They had there a view of the Dock End in Whitby's palmy days. This peep of Whitby when alive with shipping brought more visitors to Whitby than anything else. The late Mr. George Weatherill was never tired of painting it, and it had been painted by thousands of other artists. Its charm was, he believed, owing to the fact that there they had one distance gradually falling back behind another; the eye can travel by easy stages from the boats in the foreground up to the Abbey and sky behind. But what had they now? (Here was shown a view of the Dock End in its present delapidated state.) What met the eye of any artist who had heard of this beautiful view? This photograph was taken a fortnight ago. Just now the Urban Council and the Harbour Board imagine that the Dock End sewerage smells worse than ever it did. It was not their noses which were really affected; it was their eyes which were hurt by the sight of all this delapidation.

After some humorous remarks respecting some of the buildings on the Dock End, the lecturer proceeded to say that one of the foulest blots on Whitby's fair page - which, if not stopped, would surely drive people away to places where such things were not allowed - were advertisements. The people who lived here all the year round had got used to those sort of things, but they must and they did shock our visitors, who were constantly expressing their astonishment that such things as this should be allowed in a town which calls itself a health resort. If people must advertise, let them keep to the newspapers, and not push their pills and boots into our eyes at every turn. (Applause.) (A view of a house-end with an advertisement in very large letters was here shown, as were also two views of the hoarding in Brunswick Street, and one as it formerly appeared with Stockton Walk and the old game shop)

The lecturer then showed a fine chimney piece in the Old Bank in Grape Lane, and expressed the hope that when the Bank was turned into a hospital it would be left for the patients to look at when laid on their backs. He had a strong objection to iron railings, particularly in the country, where they were invariably ugly.

A view of the beautiful doorway at the new Brunswick Room was shown, and this the Lecturer said would look beautiful every time the sun shone upon it. He then ran along Baxtergate and pointed out that the fine carving on the Post Office and new bank was lost through being on the shady side of the street.

After some humorous remarks about the lampposts in the town, he said they ought be truly thankful that the country was not occupied by townspeople, or they would not have had a tree left; if the country people had a fault it was that they seldom planted a new tree, even if a tree died or was blown down, they did not replace it with a young one. Thousands of people came here every year, rather for the beauty of the surrounding country than the enjoyment of the niggers (sic) on the sands, or the round-about on the Abbey Plain.

The country about them owed its beauty to the fact that it had been left alone. How many thousands would go up to Glaisdale to look at Beggar's Bridge, if it were a modern iron one ? - not half-a-dozen. Yet, one heard that this old link of the past was to be removed, because it was not wide enough for a coach and four. If the Bridge was unsafe, by all means improve the ford or build a new bridge higher up the stream ; but to pull down this Beggar's Bridge would be unpardonable vandalism.

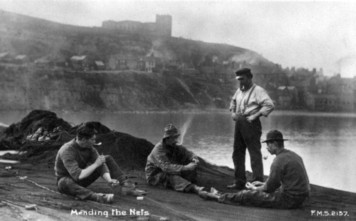

Several pictures of fishermen and fisherwomen were shown, the lecturer suggesting how much more picturesque the men appeared in sou'westers, and the women with shawls over their heads, or sun bonnets.

After reference had been made to some choice bits of country scenery round about Whitby, which were thrown on the screen, the lecturer said there was one thing which the natives of Whitby did not see so much beauty in as dwellers inland did. He meant the sea. In fact, it was difficult to enter into the feelings of inland people with regard to the sea. If they could only spend say a year in prison, and be shut out from the sight and sound of the sea they might feel, on their release, the wonderful companionship of the sea. They must have noticed how people from inland towns went as near to the sea as possible when they first approached it; most of them went into it, and many sat on the sands all day long looking and listening to the bursting of bubbles of air as the breakers rolled over and over. (Several seascapes were shown, also a sign post on the moors.)

Mr. Sutcliffe concluded by saying that beauty was to found everywhere, if they only looked for it. Even in the most barren place very often all they had to do was to raise their eyes from the ground, and the heavens at once declared the glory of God. (Loud applause.)

About fifty pictures were thrown upon the screen during the evening, some of these being reproductions of Mr. Sutcliffe's famous pictures, notably the big wave at the West Pier end, Beggar's Bridge (in winter), the Sign Post on the Moor, &c.

The lantern was ably manipulated by Messrs. A. McNiel and T. Adamson.

The Rev. G. M. STORRAR, in proposing a hearty vote of thanks to Mr. Sutcliffe for his lecture, said Whitby owed a debt of gratitude to that gentleman for his beautiful advertisements of the town and district by means of his photographs. He trusted that some of the remarks they had listened to would be borne in mind and that in their improvements the natural beauties of the town might have consideration.

Mr. J. REED seconded the vote, and it was carried with acclamation.

Mr. SUTCLIFFE, in acknowledgment, said he hoped at some future time to have another opportunity of addressing them.

Borrowed from the Old Whitby Facebook page. Edited and posted by Mike Wade.

|

|

|

|

|

If you should spot any broken links or spelling mistakes on this site, we apologize and ask if you could kindly send an email to haglathe.house@gmail.com telling us about them. Thanks.

|